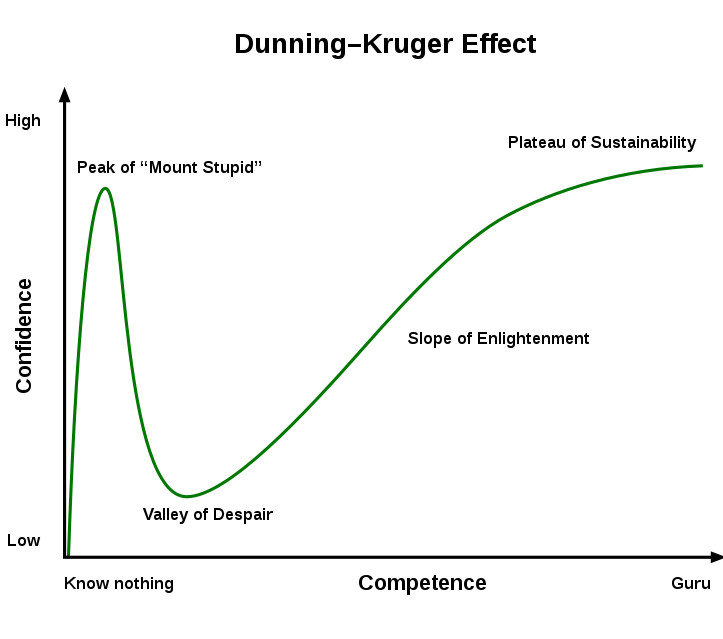

The Dunning Kruger effect can be applied to the totality of knowledge in any given domain, as well as the knowledge we have in relation to knowledge itself, or our own personal epistemological standpoint. The Dunning Kruger effect describes a process by which we undergo in the relation between “actual” knowledge, to our confidence in knowing. In a typical skill with which we have no knowledge, our confidence in our knowledge is close to zero, as we recognize complete ignorance. As we gain a small amount of knowledge, we are lead to the illusory belief that we have made much more actual progress in knowledge than we actually have in the domain, and our confidence in the acquired knowledge and competency in respect to it is extremely high. With this little acquisition of knowledge, in comparison to our original state of absolute ignorance, we are lead into the belief that we know much more on the topic than in reality we do, and this false belief leads us to a sense of overwhelming confidence in knowledge on the subject. After more time, experience, and knowledge is gained in the subject, the more complex and intricate its nuances become, the less confident we become in relation to the knowledge. After the initial point of simple conceptualization in the domain of said inquiry, all additional knowledge serves to prove how increasingly complex the topic truly is, and our confidence in the totality of knowledge of the subject generally degenerates as we see ever increasing pathways for growth, and an ever opening field of ignorance in relation to questions that are yet to be answered in the given domain. After continual study in the domain, our confidence reaches its lowest peak, as we become baffled by the amount of content yet unknown, and we undervalue what we do know in relation to the unknown. As we gain in knowledge, it seeks to illuminate the amount of ignorance we have in regards to the subject. There reaches a point when a broad foundational knowledge structure is established, and from there, we can begin to explore further areas of inquiry in relation to the domain of knowledge in whatever aspect it may be that we are attempting to gain in knowledge. From this bottomed-out valley of confidence in knowledge, we make the actual relational confidence grow, as our knowledge grows from this point, we slowly gain in confidence as to what we actually do know on the topic. The relation between knowledge and confidence at this point becomes more honest, and now, with an increase in progressing through additional knowledge in the domain, we grow in corresponding confidence of knowledge in the domain.

On a life size scale, the teenage years reflect the state of original boundless confidence in our knowledge, as we have reached the age where our set of knowledge in the total domain of knowledge has increased rapidly, the “beginner’s gains” have been acquired and we are led into the false supposition that we know much more than we actually do This explains most teenagers reluctance to parental and authoritorial advice, as they believe the knowledge they have is sufficient in answering life’s questions, and in navigating its landscapes. As the teenager continually experiences life, and grows into his twenties, where more complicated and nuanced life occurrences take place, the less his confidence becomes as his recognition of his own ignorance in so many topics grows. It isn’t till the individual has set himself on a stable, foundationally firm, course in life, after many chaotic elements have been ordered, many unknowns become known, that the process of honesty in the relation between knowledge and confidence grows. It seems like in the early twenties most people have a sort of existential dilemma, as their confidence has so dwindled that the sense of purpose, and how to navigate the future, is wholly unestablished. Once these questions have begun to be formulated in the young adult’s mind, he can work towards the relinquishment of the existential dread, and can seek to find what a truly meaningful life would be like, to him. In this way, his knowledge in the set of all domains begins to crystallize into a formulated conceptualization of what his purpose is, what a future he would like to exist for himself would look like. As career, relationship, shelter, hobbies, and interests begin to be decided upon in their direct evaluation in relation to the individual, he can begin to make progress towards that ideal possibility of his projected future self. This self-knowledge, and the basic defining and differentiating of values, allows the individual to make knowledge and experiential progress towards the goals. At this point the valley begins to ascend in the direction of the ideal peak. As he makes progress in the domains of interest and importance he has uncovered as being valuable to himself, he begins to grow in confidence as his competency and knowledge in these valuable areas of inquiry increase. Thus the dunning Kruger effect can, metaphorically, play itself out, to differing degrees, in the life cycle of the developing psyche, and the life attached to it.

The more you learn about the world in any of it’s aspects, the more you begin to realize how complicated it is. The growing understanding of the complexity in the world at every level, macro to micro, in every field of study, doesn’t necessarily make your subjective life more complicated. It is possible to have a grasp of the situation of reality, in admitting our fallibility and ignorance, yet still have a stabilized psyche that is content with the knowledge of the individual’s own ignorance. The deeper down the rabbit hole you go, in any direction, opens you up to see just how many different perspectives there are to see any objective fact, and how deep knowledge can possibly run, ad infinitum. The important knowledge to learn is how to wisely conduct yourself among this reality you are becoming more capable of understanding, and a big part of it is in being satisfied with your existence and not becoming overwhelmed in the unending stream of phenomena always arising in your experience, and rather keeping your desires pointed towards an ideal aim and distractions from that aim to a minimum, as you strive on diligently toward your goals. This will not only reduce suffering, but allow for clearer thinking, leading to a better more articulated understanding of reality in the future, and altogether a greater sense of purpose and wellbeing in relation to what could otherwise have been the case.